1 …

I always referred to it in writing as “CHCMC” (a bit of a mouthful, that acronym) or in speaking simply as “Clifton Hill”, as if it were the entire suburb involved! Some others called it the “Clifton Hill Music Centre”. (40 years later, a person in their 20s referred to it casually as the “Clifton Hill Machine Factory”!) But notice that what went missing mostly, was the “Community” bit, which evokes music classes and multicultural folk concerts and the like. And there was (as I now see, reading Ernie Althoff’s 1989 online memoir of the place) some of that, apparently, at the very start in the later 1970s, but such community groups soon “drifted away”, and the scene (as it was so often called, and as I still like to call it) formed its character more around what was then known (vaguely, to my eyes) as “New Music”, or the various kinds of experimental music, from classical-experimental (including the then-latest developments in computers, synthesis, etc.) to pop-experimental (New Wave, post-punk).

It is always fascinating to look into the holes or clouds in one’s own memory. I still have very good (if not exactly total) recall in my early 60s, but I realise now that there is a certain fog around some Clifton Hill details from 40 years ago. Intriguingly, this mist mainly relates to the physicality of the place itself. I cannot call up in my mind the various routes I took to get there by public transport (while living in Fitzroy in 1982, I must have walked there often) — i.e., when I wasn’t being driven there by friends — and I would find it hard to draw a precise map of the place itself in all its physical details. It was a jolt even to see, in my old notes, the actual address of it written down, something expunged from my head long ago: 6-10 Page Street.

What I mean to say is, the place to me is (was) a kind of dream, and hence its materiality is fuzzy. It is almost a kind of magical, fantasy house for me — sitting in the middle of that leafy, sleepy, residential street, as it still was in 2010 to 2012 when I lived in Clifton Hill — like one of the “secret places” in Jacques Rivette’s films, where you must go more and more inside it to find the hidden core … The intensity of certain experiences I underwent there, its significance in my young life, is so great that some of the mundane banality of it is blotted out. I lived it so strongly and immanently, I have no memory of some of it! It’s a pleasant kind of haze for me, even though I rationally know that, week by week, it wasn’t always so lovely or entrancing or entertaining. But my overall impression is a very positive one.

Ernie’s memoir brought back a few of the layout details. A ground floor, which I almost never saw in use, except when John Dunkley-Smith did a spectacular set of “simultaneous projections” on loops, across screens and walls. That was mighty impressive! I wrote about it 20 years later, in a retrospective catalogue essay for John. And then there was upstairs – but I don’t remember the stairs themselves I walked many times to get up there with everybody else.

I do remember the small set of steps leading to the (totally empty & tiny) bio box upstairs — they were easy to fall off. And I do remember vividly the stage and audience seating space, I especially remember it from the POV of performing on it, rather than from a spectator’s POV (although I was far more often spectator there than performer).

I always loved (perhaps naively) the basic acoustics of the place, and I especially loved the binaural audio recordings made by Ernie each week — that techno-dummy-head sitting in front of the stage —with Ernie working his tapes in the front row. I ended up hearing a lot of the back catalogue of Tsk Tsk Tsk tapes made that way, and I have an especially keen sense-memory of listening, on a long interstate train ride, to Ernie’s recording of an early Essendon Airport gig which had David Chesworth on a flattened-accordion type of cheap organ (amplified, as I remember, by clamping headphones to the top and bottom of the thing, and using that as a mic; there was no output jack!), Paul Fletcher on brush-stick drums, Robert Goodge doing simple wah-wah chords, and Ian Cox on plaintive sax or clarinet. It was great! I can relive this sensation right now, totally vividly.

As I’m sure everyone involved will recall, nobody had to pay to get into Clifton Hill events — perhaps there was donation-box or cap or something? Although we all swiftly got the label of being “elitist” — that always signals something interesting, some critical mass is actually happening; there was absolutely no blockade against anyone getting a spot on the program, every proposal was duly accepted; there was no committee decision, no editorialising of any kind. Anyone could play, or present anything.

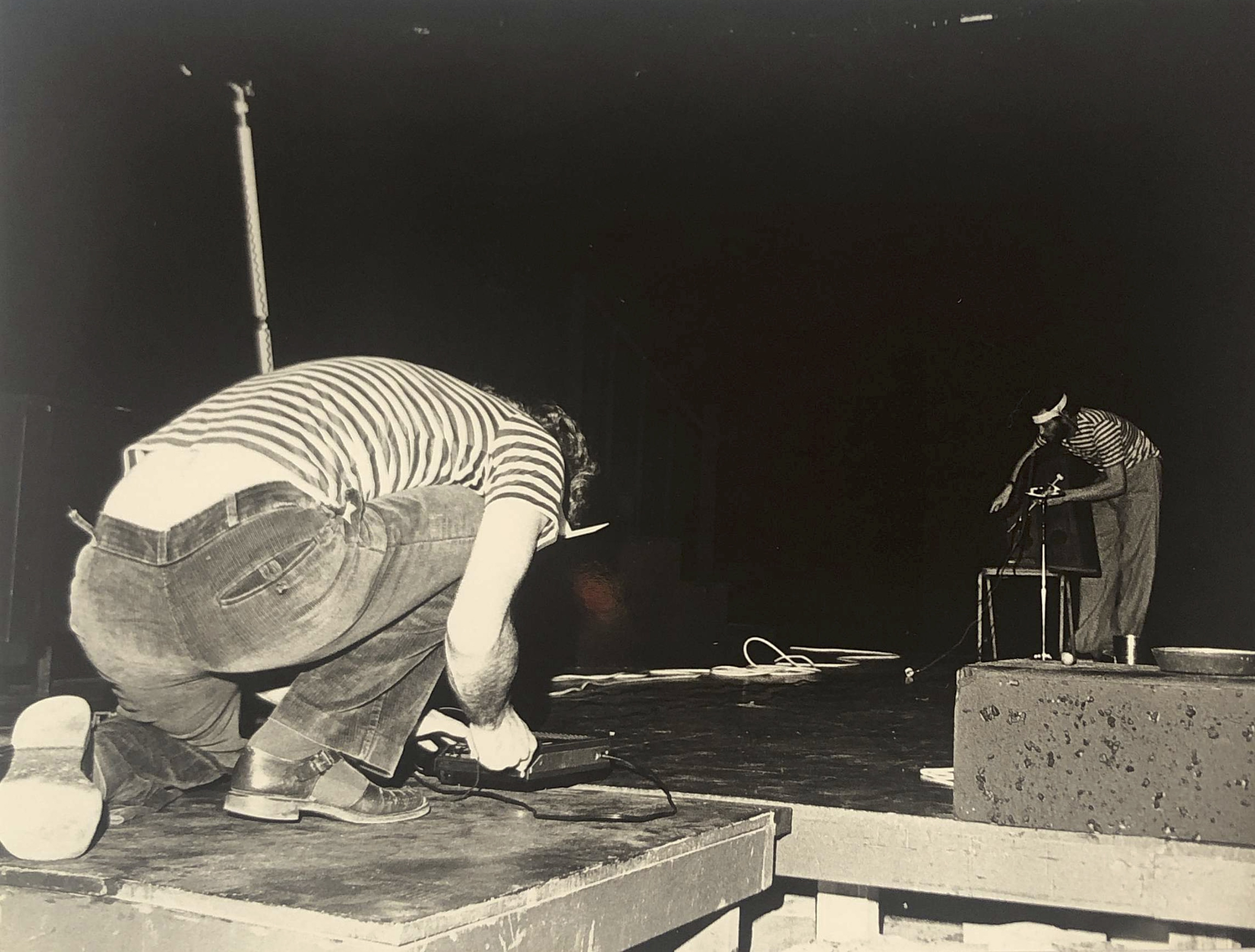

But there was a certain price to pay for this precious freedom, or at least a firm, material responsibility that every participant had to take upon themselves. What I mean is: the upstairs space had no hardware whatsoever. Maybe I am now imagining this as a kind of primal Clifton Hill myth, but I seem to recall that somebody — not a regular performer — showed up one night and, totally befuddled, demanded to know: “Where’s the sound system?” There was none! People had to scrape together their own amplification (and rough ‘live’ mix or balance of elements), there was a lot of borrowing of other people’s amps — I know that’s how I had to work, I never had much of that stuff.

So this was really the most amateur, lo-fi, low-budget, everybody-in-and-giving-a-hand moment of the New Music scene as manifested at Clifton Hill. Later — from my point of view, at least — things professionalised more as people played in pubs and clubs, and a genuine mixer-person, familiar with what you did, was needed at the desk. My efforts with The Connotations (essentially me, Gerard Hayes & Kim Beissel) suffered at this level: I remember a horrendous night at the Crystal Ballroom where we were at the mad mercy of a mixer (Chris Wyatt) who had kindly offered to man the desk for us, and then proceeded to bombard us with every kind of reverb-delay tape-loop thingy he could whip up for his own amusement on the spot. We couldn’t even hear or keep to our own beat!

The ad hoc, lack of technology situation at Clifton Hill led to occasional catastrophes, and these I remember well: a slide projector whose carousel plummeted to the floor the moment I started it up for a performance; a move across the stage that ripped all the wires out of a speaker (filched from my domestic stereo system!); a cable that couldn’t be successfully removed from Robert’s guitar amp in the middle of an instrumental keyboard piece I was doing with Gerard. These disasters came with the territory! But, in my memory, we all muddled through, one way or another; the audience would wait for you to re-equilibriate!

Performance pieces were often a kind of patchwork of diverse elements and inputs: Chesworth and Ruth Williams did a little jig-dance as Gerard and I played and sang a solemn arrangement of the nursery rhyme “In and Out the Window” at the end of one our more minimalist sets.

I’m shocked if there’s the myth formed in anybody’s head that Clifton Hill audiences never applauded, and were too cool for school! In fact, I found the audience really quite warm and receptive, especially given the generally challenging kind of work presented there. There were many regular audience members, both performers and simply spectators (see my list below). We all premiered or workshopped our new stuff there first, before venturing out (if the invitations existed) to rock clubs on the one hand, or art events on the other — where the audiences were far colder, and sometimes even pretty hostile.

That is to say — and this is a big part of my warm, fuzzy memory of the time — CHCMC was really a safe space where one could try out anything, in a first-draft form. That was precious. In fact a bunch of things I offered there, such as the slide-and-tape pieces (almost entirely lost when I left Sydney in 1987, although I have reconstructed some narration texts) were never performed anywhere else ever again.

I have powerful memories of shows/sets that really moved me, very emotional experiences — it wasn’t all cold conceptualism, no matter how we may have tried to keep its analytical presentation (more on this below) rational, intellectual and cool. Seeing Jane (later Jayne) Stevenson’s Super-8 films Italian Boys and Dreams Come True, or Maria Kozic’s Manless projected large (after I had worked on the latter in her and Philip Brophy’s loungeroom) were just incredible experiences. The earliest image-and-sound presentations by Paul Fletcher, his first works in animation, were amazing. Same for the unveiling of the various phases and stages of Essendon Airport’s new material, or “Wartime Art” by Tsk Tsk Tsk: again, I have such a visceral memory of Philip’s thundering drums, Maria and Leigh Parkhill adding synth percussion, and the imposing row of three saxes (Ernie, Kim and Ralph Traviato) blaring out “The Twelve Days of Christmas” — and that was, if I recall correctly, performed on a hot Xmas night! Magical stuff. The stuff that dreams are made of!

2 …

Let me backtrack and put a little chronology and other background info into this memoir.

I first showed up as a Clifton Hill spectator sometime in 1980, in the first half of that year. I was 20. I never held any administrative position at Clifton Hill. It was film rather than music that brought me there in the first place, my first piece of public writing directly about the place was a report for the Sydney tabloid Filmnews on the film season during the first months of 1981 published under the title “Little Films We Made” (not my original, sober “New Cinema at Clifton Hill”). I also have in my archive a previously unpublished discussion-piece about that same season, now available on this documentation website. Before that (end of 1980), I had reviewed “Wartime Art” for the Centre’s more in-house New Music publication. Through Rolando Caputo (a La Trobe postgrad at that time and co-discussant in the film season piece, whom I had met at RMIT/3RRR film discussion events), I was introduced to Philip & Maria at the State Film Centre during 1980. I attended CHCMC all through 1980, and (in a fit of inspiration!) started performing with The Connotations in early 1981 (that took a lot of rehearsal and preparation, trying out and losing various people until the basic band gelled).

1982 was my peak year for doing stuff there, and feeling that it was the epicentre of some scene of activity when it intersected in the public mind with Art & Text, the POPISM exhibition, all of that. So it was around 1980 and ‘81 that I got to know the members of Essendon Airport, and others. In 1983, there was a cessation of activity at CHCMC — it was closed for 6 months of building repairs. Things were petering out during 1983 when Andrew Preston took it over, and it was all wrapped up in early 1984. Maybe my final band Miracle Filter played at one of the last nights in ’84.

So, arriving in 1980 meant I had already missed a lot of the Centre’s prior history under Ron Nagorcka (who I hardly ever met or interacted with). Warren Burt was probably the most visible and vocal presence who hung on from that time, more on him and me below. Ernie (who I also knew from his work at the Cinema Papers office) was always very friendly and a kind-of bridge between everybody, no matter their artistic or intellectual differences. This is what made me surprised, years later, to read Ernie’s expressed intense antipathy for the “French theory” gang at Clifton Hill — of which I was surely one of the head honchos!

Arriving in 1980 also means that, in a very crucial way, it wasn’t even primarily a music venue for me. It was always, coming in at that precise point, a mix of music, performance art, film, video (I recall the video work of Randall & Bendinelli, Randelli for short. Where did those guys go?), music-plus-trippy-road-movie-projections (by Laughing Hands), and writing as well. Remember, I had already been establishing myself as a published writer (and more tentatively, a public speaker) since the start of 1979, and I remember Philip regarding me as someone who was handily “well versed in theory” coming out of film studies (I took that as a compliment!). Paul Taylor had already made the connection with me (again at the State Film Centre screenings in 1980) as a writer for his then just-launched Art & Text magazine venture, before he or I were regular audience members at Clifton Hill.

People, today, often collapse a lot of stuff together: Clifton Hill, POPISM, Art & Text, the club scene, Virgin Press and then Tension magazine (the latter launched 1983), the Super-8 Group, Juan Dávila queer art videos, Little Bands, sound art, political community art, Cantrills Filmnotes, conceptual architects, Hugo Race’s band Plays With Marionettes, the annual Surrealist Festival, the Fashion Design Council (FDC) — but really it was (from my perspective) a lot of very diverse threads coming together at certain moments and then falling apart and then re-threading, and all of these things spaced out over a five to seven year interval during the ‘80s, with a lot of changing states and phases, alliances and break-ups, in-between. (I have a vivid memory, for instance I can still hear one of the songs in my head! of Philip & Maria doing a pop demo, a hyper-ironic ditty with them both on vocals, titled “Let’s Get Married” produced by “Ross the Boss” Wilson of Daddy Cool fame. One of those moments when “the mainstream called”, and then quickly hung up!)

I’ve mentioned the warmth I felt from a regular Clifton Hill audience. I am trying to see into the crowd now and remember who was there — no easy feat. But some faces and names are returning to me, the more I concentrate on it.

There were many who were not performers in any sense at all, but really gave a life and flavour to our scene as very faithful audience members, open to anything and usually appreciative. Linda Baron (she was truly the social glue of the whole scene for quite a long time) and Peter Lawrence (though he always looked at us with suspicious “rock-n-roll eyes”!), Rolando and Lino Caputo, Paul Fletcher’s sister Jo, Vivienne Archdall and Philip Morland, that very mysterious rock-journalist Robert Lewis in natty glasses who appeared at every event, the brother-sister team of Michael & Barbara Agar, the ever-loyal Stephen Goddard & Sue Goldman … Ashley Crawford and a few others from the Virgin Press/Tension gang (like Robin Barden and Terry Hogan) must have hung around sometimes, although my impression is that they wandered in a bit later, and mainly in the rock club or art world extensions of the scene … also Janine Burke (close friend of Paul Taylor). There was Teresa DeSalvo, who died tragically young; she was from the art school context of Jayne and Philip, and appeared in the Tsk Tsk Tsk multi-monitor video performance-installation A Non Space.

There were artists (Philip Tyndall, John Barbour, John Nixon, Vivienne Shark LeWitt, Linda Marrinon — both of those last-named were and are major Australian artists to emerge then) and influential curators, especially Judy Annear, Denise Robinson, Jennifer Phipps, plus (a little further out in the circle) the style brigade from 3RRR of Julie Purvis and Merryn Gates … Paul Taylor, of course, always seemingly at the hot centre of everything going on — and even a representation occasionally from the Style Council itself, architect Michael Trudgeon (from the Laughing Hands/Crowd magazine set) or the famous Robert Pearce of the FDC who died far too young (in 1989), a victim of AIDS.

I remember feeling during the peak period (in my experience) of 1981 & ‘82 that some people came selectively — maybe too selectively — to support only their special friends, with no curiosity about anybody or anything else that was going on. That’s inevitable, even understandable, in any complexly splintered arts scene such as Melbourne’s.

My overwhelming sense is that all, or most, of these people were very tolerant of what we called the militant dilettantism of that period: the idea that we could all dabble in everything, music, film, graphic design, video, performance (we all tended to do those frozen-gestural-pose performances that I still see groups of cool young people doing today: where did we get this theatrical mode from, I wonder? Yvonne Rainer?), writing, theory, even fashion design (Jayne and others got into that for a while). Amateurism, for a time at least, did really rule the roost, and proudly/defiantly so, at Clifton Hill. I only very occasionally ever got a whiff of superior disapproval from more professional sensibilities.

I remember the bemusement from someone I deeply respect now as then, Ted (Edward) Colless, wandering into the Essendon Airport/Connotations set at the Sydney College of the Arts (where the Slugfuckers with philosopher Terence Blake, now a pal on Facebook, also played) in 1982 during the Biennale, and merely commenting on the “grinding repetition” of it all that was no doubt aiming to produce a higher, numbed consciousness in the listener! (Ted spent years, in his various articles on Super-8 cinema and other amateur transgressive arts, mocking the militant dilettante tag that I more or less coined, bless his soul!)

I tend to look at the constitution of cultural scenes such as the Clifton Hill crowd through the grid of universities and their courses at any given time in any given city or state, when those facts are relevant (as they certainly are here). La Trobe, of course, had the major feed-in at the start of the Clifton Hill adventure; if New Music courses were being promulgated elsewhere, I never heard about them, or whoever was running them. That La Trobe feed-in continued all the way through: Kay Morton, for example, and her friend Bronwen Price. Even there at La Trobe, it was a film/music crossover in both experimental practice and theory, since Brophy Goodge and Chesworth were all doing Cinema Studies under influential imported theory gurus, Sam Rohdie and Lesley Stern (both of whom have since passed away).

There must have been Darren Tofts lurking as a Swinburne Humanities representative, because he had grown up as a teen with both Lino Caputo and Leigh Parkhill, and he wrote retrospectively about those years — but I didn’t get to meet or know him properly until late in the ‘80s.

I have a sense, which I more or less verified at the time, that the very snobbish Melbourne Uni/Farrago crowd kept their distance from Clifton Hill (Gerard Hayes was a true-blue working-class alumnus of that place, but his years there had been 1976-1979) – it was only later that Virginia Trioli, for example, waltzed into the general post-Clifton Hill scene around 1984 or 1985, in the company of the Popist-type painter Chris van der Craats (he has a website, “A Speck in Cyberspace”, and is still producing work). But I also remember a night of techno sci-fi electronic music and video clips from Lisa Dethridge and friends (Melbourne Uni types) at Clifton Hill. As I said, the doors were open to anyone, even those nominally hostile to us!

The Monash and RMIT circles mainly stayed away, although I do recall RMIT’s Catalyst student magazine editor, Mark Worth (1958–2004), taking some interest in the scene and getting me to write for him over a few months (I wasn’t even a student there!). I also remember that he gave me a big speech in his RMIT office about how we all come from the Velvet Underground, but some of us are rock’n’rollin’ Lou Reed-people (him) and others are cerebral John Cale-people (me and, by extension, all Clifton Hill eggheads!).

There was a big wave coming from Melbourne State College (later Melbourne College of Advanced Education, and still later just the Education wing of Melbourne University), where I was teaching (heavily, and for pitiful pay) from 1982 to 1985. I guess I had something to do with that migration/influx of the cool and beautiful young crowd of budding educationalists! So many people came — most of whom were my students for the short or long term — from the Melbourne State source (I used to relentlessly promote CHCMC events during my classes): Sonia Leber, Anne Carter, Tim Stammers, Melanie Brelis, Alan Vandermeide, Althea Bartholomew (now gone), Ruth Williams, Glenn Bennie (who knew he was destined for such cult stardom with Underground Lovers?), Michelle Wild, Di Emry (she hired Essendon Airport to play her outdoors-at-home 21st birthday party, and later appeared in a Randelli art video around 1985/1986) – and Vikki Riley (1962–2012), who also dragged along some slightly reluctant folk from the (generally antagonistic to us then) post-Little Bands scene, such as Gavin Murray (also gone).

I vividly remember, when some situations and ephemeral alliances were really coming apart in 1983, that Gavin, with whom I was hosting a rickety and short-lived radical live radio show on 3RRR called Shrapnel, went on air in an angry, drugged haze to denounce “all this POPISM/Tsk Tsk Tsk/Art & Text/Clifton Hill … SHIT!”

Other cultural influences and intersections, beyond (sometimes overlapping with) the university sphere. There was an Arthur & Corinne Cantrill connection, a bit tenuous at first (they were suspicious, initially, of the Super-8 Revolution), but they eventually got on board promoting a lot of stuff happening at Clifton Hill via their Cantrills Filmnotes magazine (including some long texts by me), and presenting film/performance stuff there too, if I remember correctly. Maybe some of the Kris Hemensley/Collected Works bookshop poetry crowd (including ex-footballer Ted Hopkins, mastermind of an Art & Text parody, later the author of The Stats Revolution) drifted in from time to time (Kris ran in his avant-garde magazine H/Ear a long radio transcript discussion in 1983 about the general scene and attendant issues of the time, and I was one of the talkers there).

Another drop-in from another planet was Tobsha Learner (sometimes in the company of the intense actor John F. Howard, part of the neighbouring experimental theatre/performance scene of the ‘80s), who went on to make a thousand times more money and fame from writing than I, alas, ever will! I have often told the story – which is absolutely true, by the way – of the night that I watched Tobsha making, at half-time, the rounds of everyone present; before each individual, she would strike a pose and defiantly, histrionically ask: “Have you heard of … [dramatic pause for effect] … Tobsha Learner?”. If that person replied “No”, she would grandly swing her body around and walk away. When she reached me and asked the Million Dollar Question, I answered: “Yes, I have”. Which gave her a chance, at last, to deliver her triumphant punchline: “I am Tobsha Learner!”

A very strange memory swims into view now that I cannot date, but I guess it might have been 1983. And it wasn’t located at Clifton Hill, but some other bare stage in some other hall. Bruce Milne, an amiable entrepreneur of the independent music scene, organised this totally bizarre “show” — maybe it was just one or two songs — where there was, no kidding, 50 or 80 people on stage, all playing at once. It was just fucking noise, nobody could hear anything! Some people sang, a phalanx of percussionists (including Gerard) pounded a primitive beat, and everybody else made noise on whatever instrument was to hand. It was insanity! Well, I recall this because it was literally the meeting/melding of all the tribes: Clifton Hill, Little Bands, dancing fashionistas, the queer-camp brigade, the Crowd scene, bloody everybody was there! A rare moment of cultural harmony, and total musical disharmony!!

Here’s a more personal angle on it all. In 1980, arriving at Clifton Hill, 20 years old, I was actually a rather shy and lonely guy, with not many friends beyond the suburb (Richmond) in which I’d grown up, and the Catholic Boys secondary schools I’d attended (that’s where I met Gerard). And I wasn’t the only person in that basic situation. So Clifton Hill represented a whole social explosion for me, a much-needed liberation at the time (however timidly, on certain levels, I lived it). I always looked forward to intermission time on each performance night, that was when I got to talk to the likes of David, Jayne, Maria, Ian, and so many others. Gerard really got into that circle too, and became close with Ralph for many years to come. It’s funny: today, every cultural venue or institution has to have its own café, bar, or at least be affiliated with a nearby restaurant; at the Centre, we had none of that. Only a water urn for tea or coffee, as I recall! But it was enough. There was no place nearby to eat or drink! I remember some of us would sometimes end up in (fairly) nearby Lygon St for pizza.

Maybe this added to our apparently puritanical image in some people’s eyes — I very well remember the slightly mocking reaction to us in Sydney of the progressively lifestyled music/art critic Jody Berland from Canada; and Canberra’s art honcho James Mollison in 1981, baptizing me & Philip “The New Puritans”! I didn’t even yet drink booze in those early ‘80s days – and definitely no drugs of any sort!

3 …

When I arrived at Clifton Hill during 1980, the whole debate about the role, function and contents of the Centre’s New Music publication was going on, and Philip was at the centre of that, as I recall. My piece on “Wartime Art” (mentioned above) was in what turned out to be the final issue, late 1980 – and I well remember that Paul Taylor’s review and interview with Kim & me about the very first Connotations performance (“Rock Journalism”) went unpublished when the following issue was scrapped (at the start of ‘81). That document, too, sits in my archive.

Anyhow, partly through a confluence of factors and partly through my own drive to identify and hence take sides, I ended up quickly becoming some kind of theoretical spokesman (on 3RRR arts programs like Wild Speculations that I co-hosted with Sue McCauley) for what got quickly caricatured as the second degree position (following Roland Barthes as appropriated by Paul Taylor — that reductive/seductive second-degree tag followed me around forever). I was part of the seminar” series at CHCMC in 1982; I was even invited to give a talk (on “The Fantasia of Structure”, my brave title) at La Trobe Music Department. I was also tapped by Paul Taylor to review David’s Layer on Layer album for an early Art & Text (a piece that became a key reference for Chris McAuliffe in his later research thesis about local art movements in this period).

In that article, I did maybe my best shot at speaking about or describing the inner workings of a musical project: my intuition, again taken from film theory, was all about how the listener/auditeur becomes implicated in, displaced and disturbed by what they hear, the aural and semantic paths they follow through your songs/tracks.

So, although coming mainly from film study and film criticism, I became both a performing musician on a certain amateur but game level (we got better and more proficient as we went on), and also some kind of music-discourse guy, for places like Art-Network (which was incredibly sceptical about us, but at least gave us a bit of page-space) and elsewhere (weird little art, craft & architecture con-fabs going on everywhere then).

The actual musical performance period that I was directly involved in went from the start of 1981 to the start of 1984, so just 3 years in all; while the music discourse period was even shorter, two years at best, mainly 1981 and ‘82. In the initial polemical heat, Warren Burt and I tended to face off as opponents (and sometimes he had the formidably yet elegantly snarling Chris Mann [1949–2018] by his side); later I came to understand and respect Warren for the fearless and innovative explorer he really was, and I think he even came to like and respect me a bit, too, as a film critic mainly. But, back then …

I didn’t think of it this way in the early ‘80s, but now when I look back and assess this Clifton Hill period (and especially my own involvement in it) I see it in a particular and somewhat self-critical way. I can easily boil down the group position that united the flank of Essendon Airport and Tsk Tsk Tsk (always, and rightly, the starring acts), and their various fellow travellers such as The Connotations at the time. It was roughly a kind of cultural semiotics stance that drove on the mantra that “every piece of music, invented or quoted, comes with a history of associations” — and the task of performance or recording was to expose, deconstruct, work over and play with those sedimented associations. (That’s the substance of my “Wartime Art” review, for instance.)

Inherent in that whole approach, but always a secondary matter for me, was the supposed collapsing of high and low cultural references (later taken as the defining mark of some specious artworld postmodernism), — but that was really a very natural reflex on our parts; we were all part of a TV generation, and a lot of song titles, essay headings, catchphrases and so on were taken straight from dopey TV ads, popular programs and formats, and so on. (I have a delicious memory of Taylor cheekily trying to convince artist Jenny Watson that her piece “Different Strokes” for Art & Text should be renamed “Diff’rent Strokes”, simply because it was the name of a then-current American comedy TV series.) That kind of borrowing was no big deal for us, however much it may have horrified certain genteel souls in the arts-opinion pages of the daily newspapers.

Our general approach was quite akin to the line in cinema theory at the time that experimental cinema had to destabilise the codes of Hollywood narrative genres like film noir, melodrama, love story – from the inside, as it were. And this movement was going on all over the world: in the New York No Wave films and music, in Scritti Politti, Material, ABC (“Look of Love”), “mutant disco”, and dozens of other exemplars. So, we were all riding that wave, triumphantly – it was (as we all said at the time) a kind of neo-Warholian consciousness, something really happening and pervading pop culture with irony, resistance, playfulness …

Here comes the self-criticism part. It is not at all true for David or Philip or Kim (or, on the other side, Warren), who have always been deeply, intrinsically musical people; but it does hold true for me and some others who were around the scene in the ‘80s. What I’m talking about is this: I elaborated a philosophically-politically instrumental approach to music, in the sense of making it an opportunistic instrument to illuminate something else: cultural codes, social meanings. I was always saying this, in speech and in print, such as in each evening’s program notes that Dunkley-Smith (as he passed through) criticised for the way that they (in his view) overloaded, overdetermined, decoded and explained everything (whereas he thought the materiality of the work itself should do that task): making music can be good if we use it to illuminate something else, something bigger than itself. This was also my chosen weapon of rhetoric in relation to art (painting, etc.) and the art world, too, where I also moonlighted (and still do, occasionally) as a commentator: art can focus something bigger than mere art.

The problem with this position, as I now see and evaluate it, is that it involved me in a hypocrisy that smells a little of bad faith: I never would have taken the position that cinema (the medium or art form that means the most to me) is important to talk about only if we aim higher or broader than the details of films themselves, in all their complexity, and go (somehow) beyond cinema to make a general cultural or political point. When it comes to cinema, I’m not instrumental in that way; rather, I become the instrument of the medium, its servant! Which is how it should basically be, I fervently believe.

I’m not saying we all have to be text-only-fixated formalists. Wider contexts are also important to shine a light on — and I note that a newer wave of practitioners (around, for instance Joel Stern and the Liquid Architecture scene) have returned to this contextual framework in their own way. But it all has to be grounded, at some key point, in the materiality of work and medium.

This is why I didn’t continue on with music criticism or commentary myself, except in very special or isolated cases; I wasn’t really inside that medium the way I should have been, the way one needs to be as a true critic. The theoretical or categorical distinction I posed in my big 1982 Art-Network piece (partly made from interviews/questionnaires with several players of the Clifton Hill scene), “Texts and Gestures”, still holds good for me today: you can regard any piece as a work-in-itself (a text), and/or as a gesture in a wider field. (The philosopher Giorgio Agamben has, since that time, brought a welcome depth and usefulness to this distinction.) When it came to my involvement in music between 1980 and ‘84, I was much more weighted toward gesture than text. Today, I would likely try to rebalance that, if I could.

And, as for actually playing music in public, although I harboured various fancy dreams and plans, everything had shifted under my feet by 1984: where people like David, Robert and Philip were really getting their act together and exploring various musical paths and projects in public (even Jayne and Ralph had their Flaming Stars band, briefly – and I remember their songs although I heard them only once, “New Pair of Pants” and “River of Dreams”), I literally had no money (and no way of getting it), no equipment, no gang of musicians around me (once I had exhausted the student pool at Melbourne State), no connections, no way of getting it out there into clubs or onto festival/art stages, post Clifton Hill.

Even after recording our Connotations EP record with David at the controls (the master tape famously lost! ) for the bottom-dollar price of the $1,000 we had earned through gigging, we then didn’t have enough dough to actually get it pressed and distributed, because that whole subterranean cheapie opportunity collapsed for our socio-economic underground sector …

So, when the Centre died, my own centre for musical operations was gone, vanished. It was, finally, as simple as that. I think something similar happened for Ralph, Jayne, Maria (although she later worked music into her “Bitch” project of the ‘90s) and many others. People such as Gerard who had mainly been there for the ride, got off the ride. The audience of hangers-on drifted across to other scenes, if they could find them. And others like Kim have intermittently tried to pursue their desire in the music area, through diverse means and channels (such as his curation of rare tracks for special re-release), as well as live performance.

In 1985, I really pledged myself, internally, to a renewed energy invested in film analysis, film teaching, and especially writing about film – you gotta recognise and seize what you’re best at, and not be a dilettante (on too many levels) forever! Today I’m still on that filmic path — and I came back to creative practice through another route, the short audiovisual essays I began making with my partner Cristina Álvarez López in 2012 (we’ve done hundreds by now). I have even started composing & recording lo fi, digitally-enabled music for some of those!

So, militant dilettantism lives on, after all.

© Adrian Martin, 24–26 July, 2019 (reworked September 2023 & June 2024)