At CHCMC

an Australian experimental

aesthetic emerged ...

Whether it was a coincidence or shared circumstances, the Clifton Hill Community Music Centre (CHCMC) emerged just as punk’s ‘just do it’ attitude melded with emerging postmodern sensibilities, which, among other things, led art-makers to coalesce in new spaces that ignored even the mainstream’s alternative venues. Although CHCMC began as a community-oriented music venue, it soon gave way to new creative, political, and philosophical pathways that artists developed and explored during its five or so years of activity. I hope that this site will be used by both researchers and casual listeners to unpack specific works, potentially revealing their significance to experimental art practice in Australia.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a notable shift occurred as institutionalised culture began to lose its dominant grip while universities underwent corporatisation and became less relevant. Concurrently, popular culture, once looked down upon within the arts, gained new legitimacy and was recognized as a rich and entangled field to explore. For some of us, unskilled in traditional art-making and disillusioned with mainstream music practices, a creative gap opened that we could fill by exploring music-making, sound, and performance; uncovering novel concepts; and experimenting with new methods that embraced our varying levels of competence.

Melbourne is a big music town, and back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, CHCMC emerged as a space on the margins of the mainstream where experiments and shifts in cultural discourse played out, both performatively and audibly, to a small but growing audience. The Centre provided a supportive space for emerging artists and their temporal art-making that didn’t fit commercial and academic expectations.

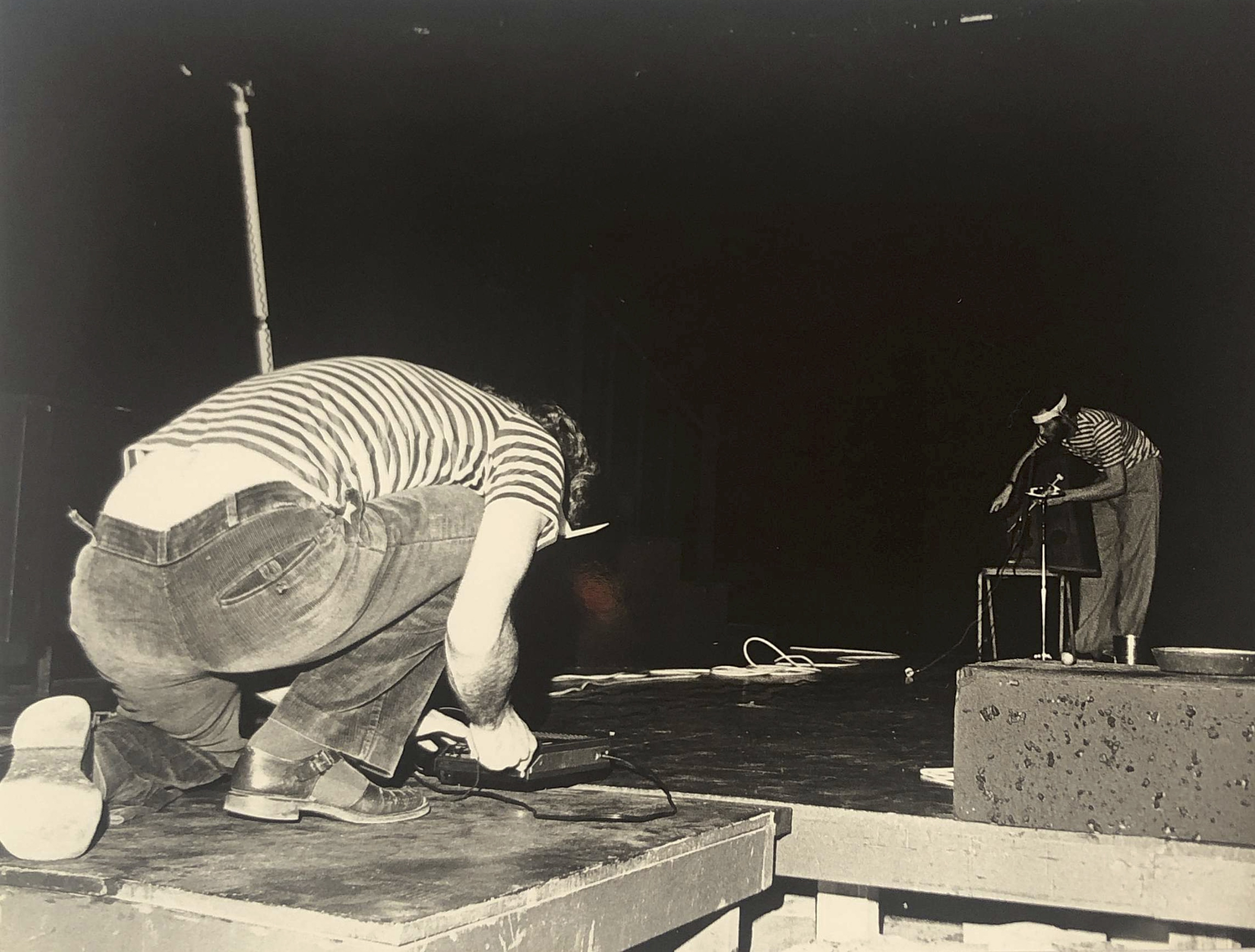

Artworks performed at CHCMC were wide ranging in scope, primarily involving music, but also performance, film, video and installation. These works de-emphasised traditional ideals of craft, expression and musicianship; moreover the artworks were often critical of the dominant channels of music and art production and their cultural framings that were pervasive in mainstream culture.

At CHCMC, an Australian experimental aesthetic emerged—one that ceased to replicate American and European ideas and trends. Instead, expressive forms reflected local experiences and themes, and had room for different approaches that included, for some artists, modernist counter-culture methods, and for others the creation of works that deconstructed what some saw as pervasive modernist tropes.

Explorations of broader topics were primarily explored, articulated, and expressed through music, sound, and moving images, rather than through written texts or curatorial frameworks. This included political and Indigenous themes—albeit from colonial-settler perspectives—as seen in the works of Ron Nagorcka and IDA. Curiously, listening back to the archive today, it is noticeable how the Australian accent became very prominent. Exemplified by figures like Chris Mann, Ernie Althoff, Ralph Traviato, Adrian Martin, and others, the natural Australian voice signalled a fresh, personal voice of liberation and expression. Spoken word still had a role to play: Warren Burt, Ernie Althoff, and Chris Mann often spoke at length about their works, prior to, or as part of their performances, and Tsk Tsk Tsk often presented short writings to accompany their performances. But the music always came first. During breaks, appraisals and critiques would take place around the tea urn.

As I now see it, CHCMC was a site where postmodernism 1 emerged in Australian art practice, although none of us were familiar with the term at that time. Initially evident among younger performers, including my own generation, this emergence involved both intuitive and deliberate deconstructions of modernist artistic and cultural methods and aesthetics, occasionally challenging the approaches of older CHCMC artists whose creative pathways were informed by a counter-culture practice that nonetheless continued to align with modernist methods. Revisiting all the works within this archive today, I find them all equally intriguing, making it challenging now for the visitor to distinguish between these two creative ontologies. Listening back, I recognise influences in my own music from older composers like Warren Burt. But it is still worth acknowledging that as these different creative approaches rubbed up against each other at CHCMC it created a creative friction that was ultimately productive for all.

My memories of this time also include non-sonic aspects of CHCMC’s creative milieu, which were still important: what we spoke about, how different people dressed (according to their sub-cultural milieu), and all the range of styles, methods and interests we all brought to CHCMC.

And so, for the keen listener, these recordings capture a dialectic of aesthetics, derived through modern and postmodern creative methods and through framings that were variously expressed through the music, performance, film and video. For example, the slightly older composers tended to experiment with inner musical structures and processes, while us younger composers concerned themselves with external structures, such musical context and the spectacle of performance.

It was a busy time. New works were being created each week, often in response to what other artists had just presented the week before. Some artists referenced contemporary American thinkers, while others experimented with novel musical concepts and structures, uncovering fresh aesthetic outcomes. For example, multiple cassette recorders were used to copy sounds from one recorder to another while also adding new sounds, in a process that gradually layered-up many sounds, transforming simple recorded utterances into dense, distorted and evocative soundscapes (Graeme Davis, Plastic Platypus, Ernie Althoff), or the deployment of novel tunings and pitch sets (Warren Burt). Some performers applied emerging film theory that was being introduced at La Trobe University and at Melbourne State College (Philip Brophy, Adrian Martin, Robert Goodge, David Chesworth, Rolando Caputo). Other performers were influenced directly by the artists who performing before them at CHCMC.

All this was taking place within a world that was still very analogue; where tapes took time to rewind and musical works and performances often emerged slowly over long timescales, and where cheap super-8 film’s grainy images evoked a visual aesthetic that now appears quaint and old in comparison with digital images. Sound Art hadn’t yet emerged as a distinct discipline or even as a term. There was no internet, no mobile phones, nor social media to disseminate what was taking place at CHCMC. Instead, the mainstream and alternative press had full control, while public radio stations were just starting to get a foothold. Some journalists harboured suspicions about CHCMC’s ‘off the grid’ activities: its motives and critical attitudes, often calling us arrogant for our dismissal of mainstream culture.

Amongst all this, I remember that we were being told that we would all soon be swamped by an incoming tidal wave of digital technology. It was difficult then to picture how this would affect us and how it would forever transform the fidelity of the mediascape, our methods, and our creative pathways, which it has certainly done.

This rare archive of a nascent experimental music scene was recorded binaurally on cassette by Ernie Althoff – himself a regular performer at CHCMC. It is not a complete record, rather, it reflects Ernie’s personal choices, after all, no one asked him to make these recordings; he simply took it upon himself to attend performances and make them. Ernie’s own creative work is therefore well represented in these tapes.

The cassettes Ernie recorded had been resting on a shelf, silently for over 40 years until 2020/21 when they were transferred and organised into a digital archive for this site The cassette transfers were made by John Campbell, who was also a performer at CHCMC (and who initially uncovered the availability of the Organ Factory and its potential as a community space). I have done some restoration work on the recordings including compiling recordings of single events that Ernie spread across several cassettes in order to fill up any available space.

Some artists who were prolific at this time are not well represented in the archive, as they mainly performed electronic music that was considered to be already documented on tape. Warren Burt, a hugely significant artist during this time has relatively few recordings made at Clifton Hill. His prolific output was at the time mainly video and film-based. We have included a separate archive of some of Warren’s work with Plaistic Platypus from the 70s that also includes undated CHCMC performances that he recorded. This can be found under the ‘Other Recordings’ link.

In the Ephemera section you will find distinctive performance season posters designed by Philip Brophy and Ernie Althoff and copies of the New Music magazine (1978–81) edited and published by Philip Brophy and myself that contain reviews of performances followed by discussions with the artists who respond to the reviews. Also included are three earlier publications of The New Music Newspaper (1976–77) edited and published by Warren Burt and Les Gilbert (clicking on the cover images of the publication will reveal their content). You will also find photos and ephemera associated with CHCMC. There weren’t many photographs taken at CHCMC, as it was considered indulgent by some of us to think that one’s contribution should be preserved beyond the performance, plus taking photos back then was expensive and we were not rich. In retrospect we are thankful that some photos were taken and recording were made. We are fortunate that photographer and CHCMC performer Jane Joyce took a range of shots that appear throughout the site, as did members of →↑→ and myself. Other photographs are being be added as they come to light.

CHCMC Performers are encouraged to send in information and clarifications and to flesh out their own biogs. If any of you have recordings of CHCMC performances that we have missed then please us know.

David Chesworth

-

Postmodernism as I define it here, was an intellectual stance or mode of discourse defined by a skepticism toward the grand narratives and ideologies of modernism, as well as opposition to epistemic certainty and the stability of meaning. ↩